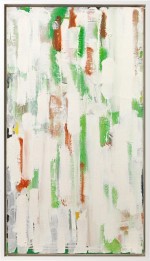

Patrick Heron

White and green upright : August 1956

Oil on canvas: 36 x 20 (in) / 91.4 x 50.8 (cm)

Signed, dated and inscribed on the stretcher: White & Green Upright / August 1956 Patrick Heron

This artwork is for sale.

Please contact us on: +44 (0)20 7493 3939.

Email us

PATRICK HERON

Headingley 1920 - 1999 Zennor

Ref: CA 240

White and green upright : August 1956

Signed, dated and inscribed on the stretcher:

White & Green Upright / August 1956 Patrick Heron

Oil on canvas: 36 x 20 in / 91.4 x 50.8 cm

Frame size: 38 x 22 in / 96.5 x 55.9 cm

Provenance:

The artist, then by descent to Katharine Heron and Susanna Heron;

private collection, 10th October 2001, via Waddington Galleries, London [B32931]

Exhibited:

St Ives, Tate Gallery, Patrick Heron: Early and Late Garden Paintings, 20th March-3rd June 2001

Literature:

Mel Gooding, Patrick Heron, Phaidon Press, London, 1994, illus. in colour p.106

Andrew Wilson, Patrick Heron: Early and Late Garden Paintings, Tate Publishing, London, 2001, illus. in colour p.27

This painting will be included in the forthcoming catalogue raisonné of Patrick Heron’s oil paintings, currently under research by Dr Andrew Wilson and Dr Robert Sutton.

This fascinating painting belongs to a key moment in the development of Patrick Heron’s abstract language during the spring and summer of 1956. Just a few months before it was painted, the artist and his family moved to Eagle’s Nest overlooking the village of Zennor

in Cornwall, an idyllic location which would immediately and continually influence Heron’s work for the next forty years. Writing in the exhibition catalogue, Patrick Heron Early and Late Garden Paintings, which includes the present work, Andrew Wilson describes the locale: ‘set on a granite outcrop some six hundred feet above sea level, with panoramic views of the Atlantic ocean to the north and moorland hills to the south. The sea acts as a mirror to the sky, affording the immediate area a most special light.’ Around the house, the previous owner Will Arnold-Forster had grown ‘a series of windbreaks to protect a garden of exotic flowering trees and shrubs among the granite.’[1]

The move from ‘the smoke and fog of London to the coastal clarities of Zennor’[2] prompted an explosion of colour in Heron’s work and the transition ‘to a fully resolved expressive abstraction.’[3] The house with its beautiful surrounding gardens was already known to Heron when he bought it from a friend in 1955. He had previously visited it as a young boy when his family house-sat for their friends, the Arnold-Forsters, and during visits to Cornwall, after the war, Heron had made a number of sketches of Zennor and the house above.

In the early months of 1956 Heron had begun a series of paintings which structure the canvas with a series of vertical, painterly strokes, chiefly in black and white, including, Vertical : January 1956 (Tate). White and Green Upright : August 1956 maintains the vertical emphasis of both canvas and brushstroke, but its luminous palette evokes the light of Cornwall, as well as the flowering azaleas, camilias and granite rocks of Heron’s garden. In amongst the predominantly white vertical strokes, Heron weaves broad taches of rich red and vibrant green, dark and opaque in areas, lighter and more diffuse in others, as well as barely visible lines of yellow and black, delighting in abstract forms which both shimmer on the picture surface and retreat into its depths. Mel Gooding describes the ‘more openly spatial, atmospheric or aerial feeling’ of these paintings with their light, quick texturing.[4]

As a writer and art critic, Patrick Heron had been contemplating abstraction since his first published article in 1945. He began to experiment with purely abstract painting in 1952, largely as a response to the first London exhibition of Nicholas de Staël (1914-1955). It was not until the winter of 1955-56, however that he started to pursue a radical non-figurative approach in a series of Tachiste[5] works that reflect a period of dramatic innovation and rapid change. These paintings preceded and in some cases coincided with Heron’s effervescent Garden series, while anticipating the elongated brushstrokes of his Stripe paintings developed the following year.

Freed from ‘that troublesome entity, the subject’ Heron felt able ‘to deal more directly and inventively (I hope) with every single aspect of the painting that is purely pictorial, i.e. the architecture of the canvas, the spatial interrelation of each and every touch (or stroke, or bar) of colour, the colour character, the paint-character of a painting – all these I now explore with a sense of freedom quite denied me while I still had to keep half an eye on a ‘subject.’’[6]

1956 was also the year that Heron saw and reviewed the Tate exhibition, Modem Art in the United States: A Selection from the Collections of the Museum of Modem Art, New York, which included works by Pollock, de Kooning and Rothko amongst others. He wrote in his review of the exhibition, which appeared in Arts, ‘My own feelings about these painters have shifted one way, then the other, since my first sight of them, as they hung in consort in the big Tate room, at the private view a month ago. I was instantly elated by the size, energy, originality, economy and inventive daring of many of the paintings. Their creative emptiness represented a radical discovery, I felt as did their flatness, or rather their spatial shallowness. I was fascinated by their constant denial of illusionistic depth which goes against all my own instincts as a painter...To me and those English painters with whom I associate, your new school comes as the most vigorous movement we have seen since the war. If we feel that far more is suggested than is achieved, that in itself is a remarkable achievement. We shall now watch New York as eagerly as Paris for new developments (not forgetting our own, let me add) - and may it come as a consolidation rather than a further exploration.’[7]

[1] Andrew Wilson, op. cit., p.8.

[2] Mel Gooding, op. cit., p.104.

[3] Ibid., p.104.

[4] Ibid., p.105.

[5] Derived from the French word tache meaning stain or mark.

[6] The artist, Statements: A Review of British Abstract Art in 1956, exh cat., ICA, London, 1957.

[7] See M. Gooding (ed.), Painter as Critic Patrick Heron: Selected Writings, London, 1998, pp. 102, 104.