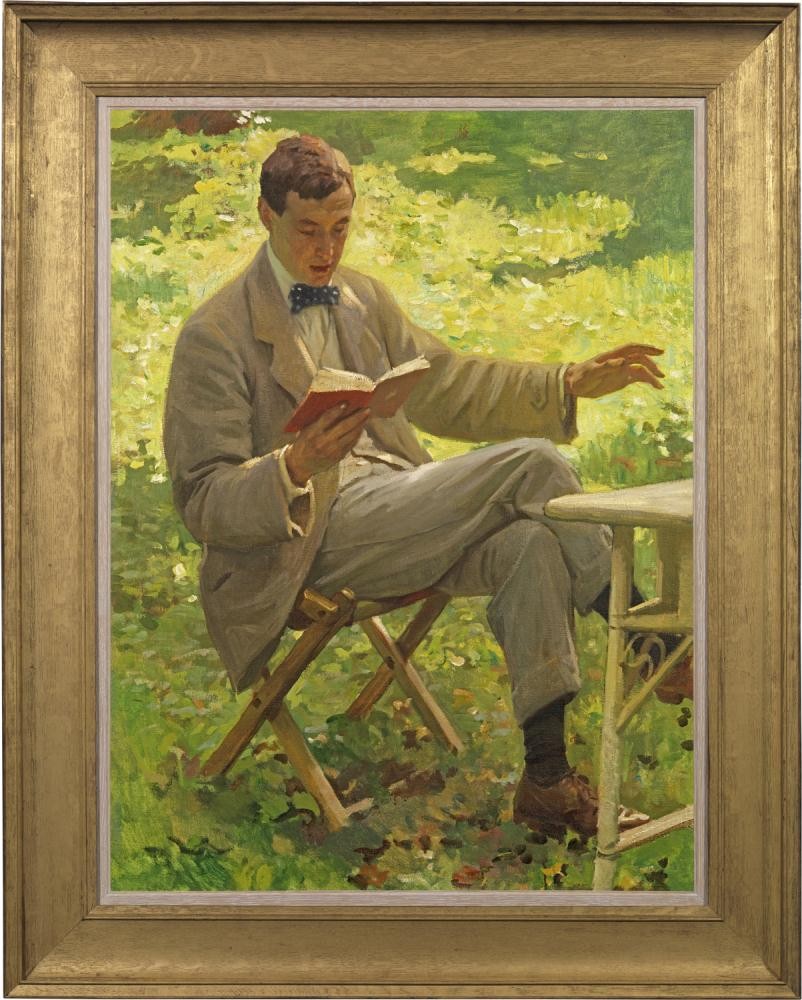

HAROLD KNIGHT

Nottingham 1874 - 1961 Colwall, Herefordshire

Ref: BG 130

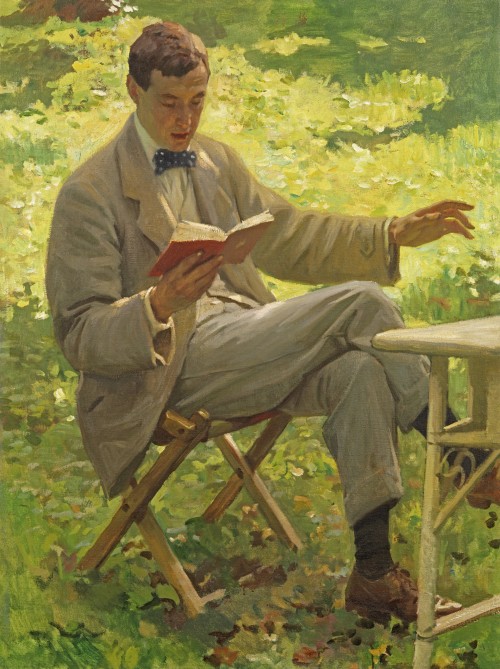

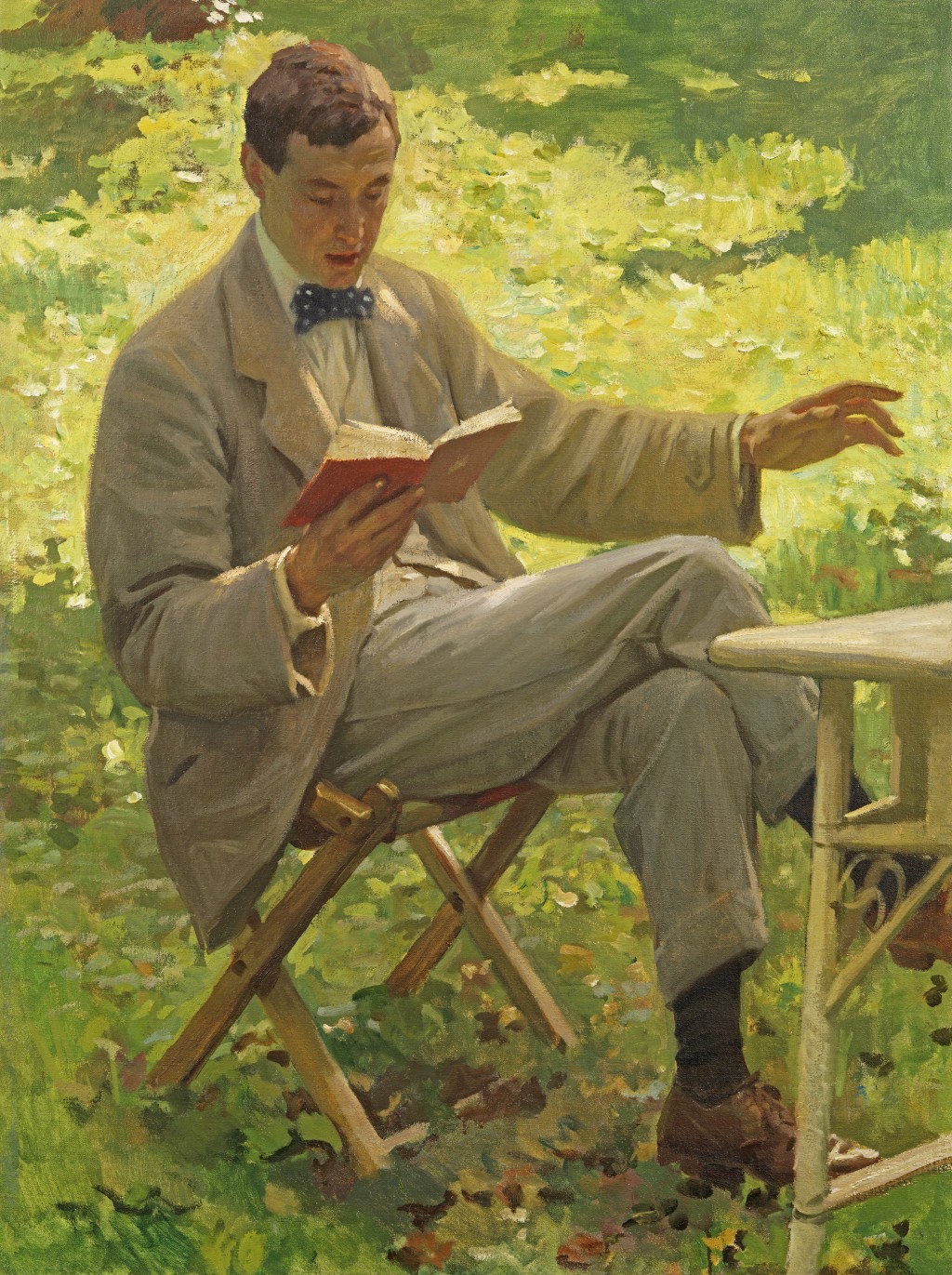

Alfred Munnings reading

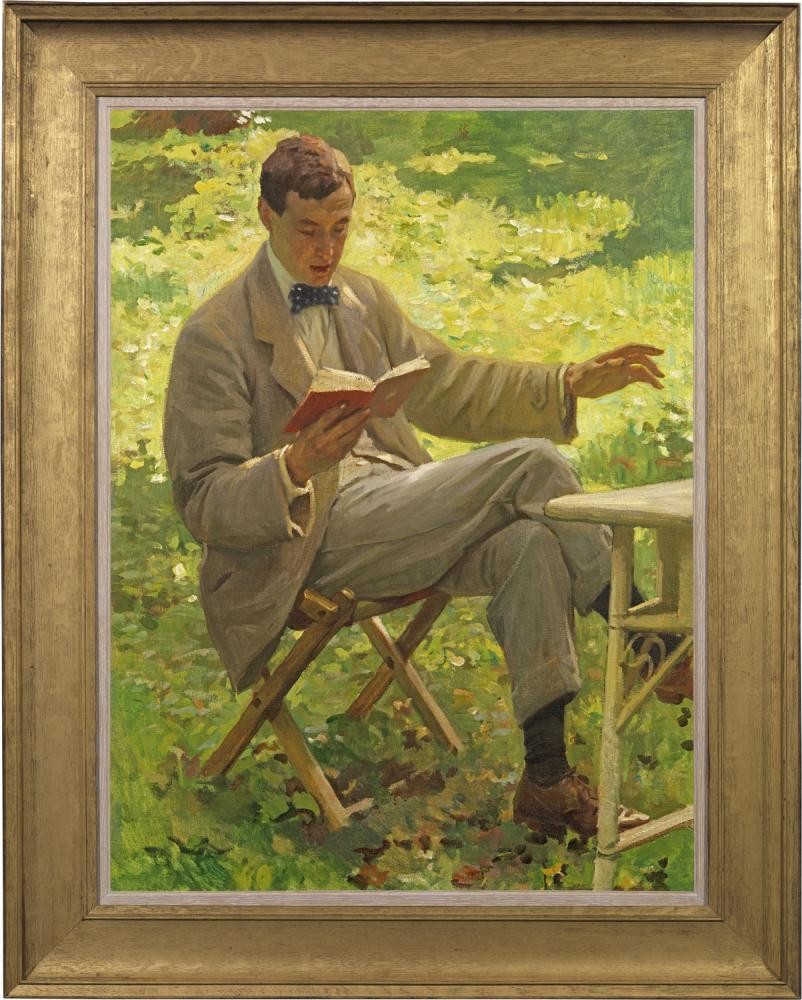

Oil on canvas: 40 x 30 in / 101.6 x 76.2 cm

Frame size: 49 ½ x 39 ½ in / 125.7 x 100.3 cm

In an antique carved ‘Whistler’ style gilded frame

Painted circa 1910

Provenance:

The Grosvenor Gallery, London

Agnew’s, London, 1936

Sotheby’s London, 9th–10th April 1946, lot 209

Private collection, UK, acquired from the above, then by descent

Exhibited:

On loan to The Sir Alfred Munnings Art Museum, April–October 2012

London, Richard Green, Sir Alfred Munnings KCVO, PRA Mendham 1878–1959 Dedham: And Artist’s Life, November 2012, no.13

Penzance, Penlee House Gallery & Museum (in collaboration with the Munnings Museum), Munnings in Cornwall, 15th June – 7th September 2019

To be included in the forthcoming catalogue raisonné of the work of Harold Knight currently being prepared by R John Croft FCA

The recent discovery of Harold Knight’s Alfred Munnings Reading (fig 1) sheds new light on a fascinating moment in the early careers of both artist and sitter. When embarking on her ballet picture, Carnaval (fig 2), for reasons that remain obscure, Laura Knight selected a canvas which was stretched on top of a work by her husband, and only when this was recently removed was the portrait of fellow-artist, Alfred Munnings, revealed for the first time. The ‘new’ work was immediately identified as being closely related to Harold Knight’s lost Royal Academy exhibit of 1911, The Sonnet (fig 3).[1]

Fig 1 Harold Knight, Alfred Munnings Reading, c. 1910

Fig 2 Laura Knight, Carnaval, 1914

Fig 3 Harold Knight, The Sonnet, 1911, unlocated

Much is known about this latter picture.[2] It shows a dramatic reading in which the flamboyant, extrovert young Munnings, known as ‘AJ’, impresses his female audience, one of whom, Florence Carter Wood, on the extreme right, he was later to marry.[3] Readings, we learn from Laura Knight’s memoirs, were, like amateur theatricals, a popular pastime in the artist community at Lamorna.[4] Munnings’ magnetism meant that

he was often the centre of attention and for Laura he was ‘the stable, the artist, the poet, the very land itself!’[5] Not surprisingly the normally reserved Harold Knight was less enthusiastic. A pacifist, he abhorred blood sports and was secretly worried about Laura’s fixation with their new friend, especially when he turned up at Mrs Beer’s boarding house, saying he had rented a room and was told that he could ‘share’ their sitting room and have meals with them. Laura records that ‘Harold received the news coldly’.[6] There may have been some relief when Munnings’ attentions were shown to be elsewhere. In January 1912 he embarked on his disastrous marriage with the unstable Florence. During their honeymoon she attempted suicide, only to be saved by Laura. During the next two years, while dogged with health problems, she formed a liaison with a local captain in the Monmouth Engineers, Gilbert Evans. The discovery of this precipitated a second, successful suicide attempt in July 1914. Back in 1910 however, Harold Knight determined to turn Munnings and his conquests to his advantage by painting The Sonnet in which the artist/raconteur is shown declaiming his verses.[7]

The action, takes place in a leafy glade, over afternoon tea – a favourite subject which resumes the alfresco settings of artists like James Guthrie and John Lavery - recalling Knight’s earlier In the spring, (fig 4).[8]

Fig 4 Harold Knight, In the spring, 1909, Laing Art Gallery, Newcastle upon Tyne

The purchase of In the spring, by the Laing Art Gallery, Newcastle upon Tyne on 7 February 1910, may well have prompted Harold Knight to begin planning a larger, more complex figure group seated around a garden table. He was at that point completing a grand interior, Afternoon tea, for the forthcoming Academy (Figs 5 and 6). This shows the artist, Garnet Wolseley posing as a butler, serving two ladies in the parlour of his house, ‘Sandycove’, at Lamorna. The lady of the house, posed by Florence, is seen in profile and dressed in green. Her visiting friend, adjusting her gloves and wearing a hat and shawl over her dark blue dress, is played by Laura Knight. A large Portrait of Florence, produced in preparation for this picture indicates that Harold Knight, where other artists might be satisfied to work from smaller notes, would execute full-scale studies of his principal figures, dressed and in pose (Fig 7).

Fig 5 Harold Knight, Afternoon Tea, 1910, sold Christie’s 8 November 1990

Fig 6 Photograph of Harold Knight painting Afternoon Tea.

Fig 7 Harold Knight, Portrait of Florence, 1910, Private collection, formerly Christopher Wood Gallery

For The Sonnet, two additional models seated in the foreground were introduced and Munnings, focal point of the composition, replaces Wolseley. As is clear from the present canvas Knight was aiming for much greater spontaneity in his outdoor setting.

Before discussing Alfred Munnings reading in detail and in view of the circumstances of its discovery, we must however consider the possibility that this is a work by Laura Knight, or the product of collaboration. Both of these possibilities have been carefully weighed and found wanting. Firstly, given her independent reputation and her proto-Feminist sympathies it seems highly unlikely that Laura Knight would have copied or produced a fragment of a composition by her husband. Secondly, although Norman Garstin’s article on the Knights, published in 1912, begins with rumination on the question of artistic collaboration, there are no other proven instances where both artists painted on the same picture – although clearly, as their intimate working practices would suggest, they were influenced by one another.[9] Finally, the existence of a further, corresponding portrait of Florence by Harold Knight, related to The Sonnet (Fig 8) tends to support the attribution of the present work.[10] Interestingly, Florence and Laura’s roles in Afternoon tea are reversed in The Sonnet, with the former wearing a large blue hat and shawl – perhaps covertly acknowledging Laura’s part as mistress of ceremonies in bringing ‘AJ’ and she together.

Fig 8 Harold Knight, Portrait of Florence, 1910-11, Private Collection

Much speculation results from the fact that a new canvas was stretched on top of the present work.[11] Laura Knight refers to materials being in short supply during the Great War, and in these circumstances it seems possible - but still extremely unusual – that the new piece of canvas was simply applied to the now discarded earlier work.[12] Yet it would surely have been more normal to detach Alfred Munnings Reading, before stretching the new canvas. Deliberate concealment seems much more likely.

Who was responsible for this? While no evidence exists to point to either husband or wife, it is obvious that both would have recognized the magisterial quality of the early work. Both had complex feelings about its conception - Harold because of his enmity for Munnings, and Laura because she wished to preserve a portrait of a man who clearly fascinated her. Since the concealed canvas found its way into Laura’s hands, it seems more likely that, of the two, she was responsible. And given the experimental nature of Carnaval, she may have thought it appropriate to use the canvas to risk new methods and a new subject matter, little realizing how important the result would be. There is no evidence to suggest that a rift occurred in the Munnings/Knight friendship after Florence’s suicide.[13] Nor is there, despite Harold’s dislike of Munnings’ heartiness, any inference that during Munnings’ marriage and after, he had designs on Laura (fig 9). While he painted his wife in an elegant equestrian portrait, Laura was merely sketched in back view.

Fig 9 Alfred J Munnings, Laura Knight Painting, c. 1910-12, Castle Museum, Norwich

For all Harold Knight’s reservations, he has found his footing in the present portrait, capturing the sitter’s characteristic ‘slump’ in the ‘campaign’ chair, and using the light and shade to pick out details of his suit, shoes and celebrated bow tie, and placing him in silhouette against the sunlit sward in the background.[14] The work’s remarkable fluency matches that of Munnings’ own painting style. Its subject and setting recall the famous scene from EM Forster’s A Room with a View (1908), in which the pretentious Cecil Vyse reads aloud from a romantic novel, disrupting a tennis match between Lucy Honeychurch and George Emerson, the book’s heroine and hero. Munnings similarly gesticulates with his left hand as he concentrates on the text, leaving us to wonder if Knight’s characterisation is not a work of gentle satire.

Written by Professor Kenneth McConkey

[1] The author wishes to thank Jeremy Cowdrey, John Croft, David and Christine Evans and Jonathan Smith for providing valuable information to assist with the cataloguing of this work.

[2] Information supplied by EL Kerr indicates that The Sonnet was apparently used as an advertisement for Players cigarettes; see Caroline Fox, Painting in Newlyn, 1900-1930, 1985, (Newlyn Orion, Cornwall), p.126.

[3] Munnings’ marriage to Florence Carter Wood, the unstable daughter of a wealthy brewer, took place in January 1912. See Jean Goodman, AJ, The Life of Alfred Munnings, 1878-1959, 2000, (Erskine Press), pp.93-105; see also John Branfield, Charles Simpson, Painter of Animals and Birds, Coastline and Moorland, 2005 (Sansom and Co), pp.50-1. See also Jonathan Smith, Summer in February, 1995 (Abacus).

[4] Laura Knight, Oil Paint and Grease Paint, 1936 (Penguin ed, vol 2, 1941), p.177 ff, records her first sighting of Munnings, surrounded by the so-called ‘Myrtage Group’ – four female students in Stanhope Forbes’ art school in Newlyn. Munnings took charge at parties, leading the group in hunting songs and reading from Dickens. See also Austin Wormleighton, A PainterLaureate, Lamorna Birch and his circle, 1995, (Sansom and Co), pp.98-9, 112-3.

[5] Knight, vol 2, 1941, p.178; quoted in Janet Dunbar, Laura Knight, 1975, (Collins), p. 82; Goodman, 2000, p.89.

[6] Ibid, p.180. Within a short time the Knights were able to leave Mrs Beers for the house vacated by the Gotches.

[7] Of the three other women in The Sonnet, two are likely to be the Knights’ London models. It is probable that the third woman behind the table was based on Laura Knight.

[8] For further reference see Kenneth McConkey, British Impressionism, 1989, (Phaidon Press), pp.7, 133.

[9] Norman Garstin, ‘The Art of Harold and Laura Knight’, The Studio, vol LVII, December 1912, pp.183-4.

[10] Private collection, see Caroline Fox and Francis Greenacre, Painting in Newlyn, 1880-1930, 1985 (exh. cat., Barbican Art Gallery), p.152 (no 152). See also no 151, a full, seated portrait of Florence.

[11] Alastair Jamieson, ‘Secret portrait of British artist hidden behind another canvas by admirer’, The Daily Telegraph, 21 September 2009.

[12] Knight, vol 2, 1941, p.210

[13] References to ‘AJ’ continue throughout the war period in Knight’s memoir, Oil Paint and Grease Paint, (1936).

[14] Munnings’ pose in the present work, is echoed in that of Lamorna Birch in The Council: Portrait Group, shown at the Academy in 1916.