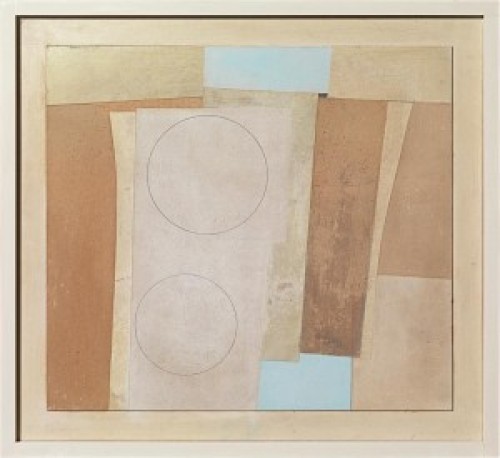

BEN NICHOLSON

Denham 1894 - 1982 London

Ref: CD 116

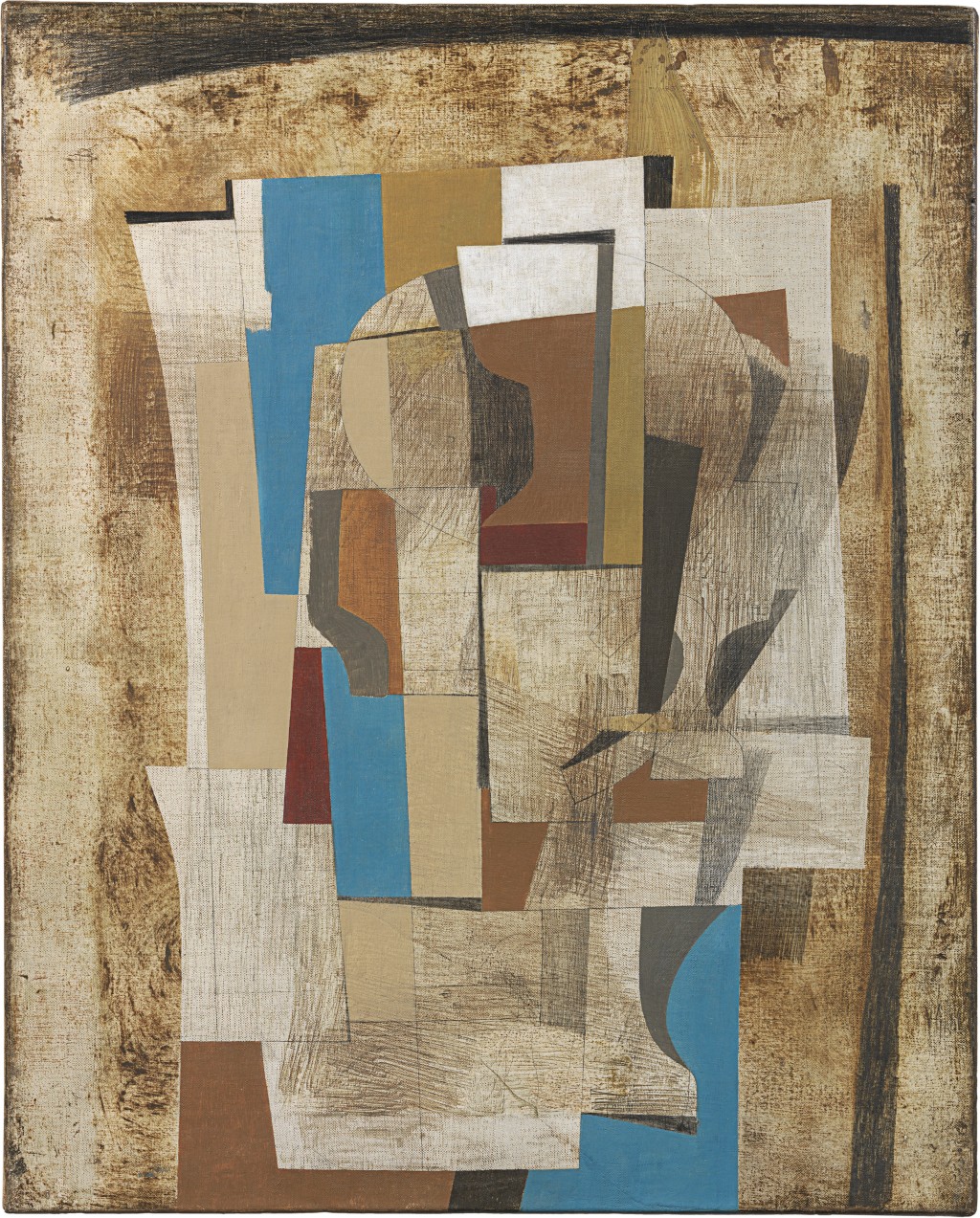

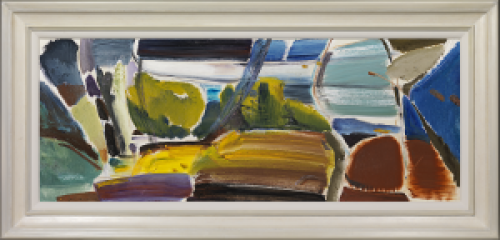

Nov 25-46 (still life)

Signed, dated and inscribed on the canvas overlap:

Ben Nicholson Nov 25-46

Oil and pencil on canvas: 24 7/8 x 20 in / 63.2 x 50.8 cm

Frame size: 32 ½ x 27 ½ in / 82.6 x 69.8 cm

Provenance:

FLS Murray, London, purchased from Lefevre Gallery exhibition, May 1947.

Galerie Beyeler, Basel

Galleria d’Arte Galatea, Turin

Marlborough Fine Art, London;

Ms Betsy Washington Whiting, acquired from the above by 1971;

Christie’s London, 3rd February 2004, lot 280;

Richard Green, London;

private collection, USA, acquired from the above in May 2004

Exhibited:

London, Lefevre Gallery, Ben Nicholson: Drawings 1921-47: Paintings and Reliefs 1921-38, 1946-47, May 1947, no.82, illus., as still life 1946 (November 25)

Hannover, Kestner-Gesellschaft, Ben Nicholson, 26th February-5th April 1959, no.27; this exhibition then travelled to Mannheim, Städtishche Kunsthalle, April-May; Hamburg, Kunstverein, May-July; and Essen, Museum Folkwang, 23rd July-30th August 1959

Baltimore, The Baltimore Museum of Art, Rembrandt to Rivers, October-December 1971, catalogue untraced

Literature:

Herbert Read, Ben Nicholson: Paintings, Reliefs, Drawings, Vol.I, Lund Humphries, London 1948, p.10, no.188, illus., as still life November 25-46, collection of FLS Murray

To be included in the forthcoming catalogue raisonné of the paintings and reliefs of Ben Nicholson currently being prepared by Dr Rachel Smith and Dr Lee Beard

‘In painting a ‘still-life’ one takes the simple every-day forms of a bottle—mug—jug—plate on a table as the basis for the expression of an idea: the forms are not entirely free though they are free to the extent that each object can be seen from as many viewpoints as you wish at one and the same time, but the colours are free: bottle-colour for plate, plate-colour for table, or just as you wish.’

Ben Nicholson, ‘Notes on Abstract Art’, 1941

Ben Nicholson’s preoccupation with the still life theme in the years that immediately followed the end of the Second World War was fundamental to the establishment of his international reputation in the subsequent decades. Reinvigorated by a feeling of liberation after six years of relative isolation in Cornwall, the paintings from this period are notably ambitious. In Nov 25-46 (still life) we are presented with a complex arrangement of objects – goblets can be identified by their distinct stems, a mug signified by the curve of a handle, other vessels suggested by precise edges and shadows – each form picked out by the viewer’s eye, before retreating to the overall integrity of the composition. As the artist would acknowledge, it was his father Sir William Nicholson that ingrained in him the significance of the still life subject, “not only from what he did as a painter but from the very beautiful striped and spotted jugs and mugs and goblets, and octagonal and hexagonal glass objects which he collected. Having those things throughout the house was an unforgettable early experience for me”.[i] Nicholson would also become a devoted collector of pottery and glassware, objects that populated both his studio and paintings throughout his career. In Nov 25-46 (still life), whilst the still life motif has familial roots, the pictorial form it takes is shaped by a cubist language – a ‘vocabulary’ that far from being a “passing phase”, Nicholson felt had been “absorbed into human experience”.[ii] In the painting objects are not fixed in a single moment in time and space, but an equivalent for the artist’s experience and encounter with these well-known forms that provide the structure through which the artist could pursue his aesthetic goal. As Nicholson would explain, “the kind of painting which I find exciting is […] both musical and architectural, where the architectural construction is used to express a “musical” relationship between form, tone and colour”.[iii]

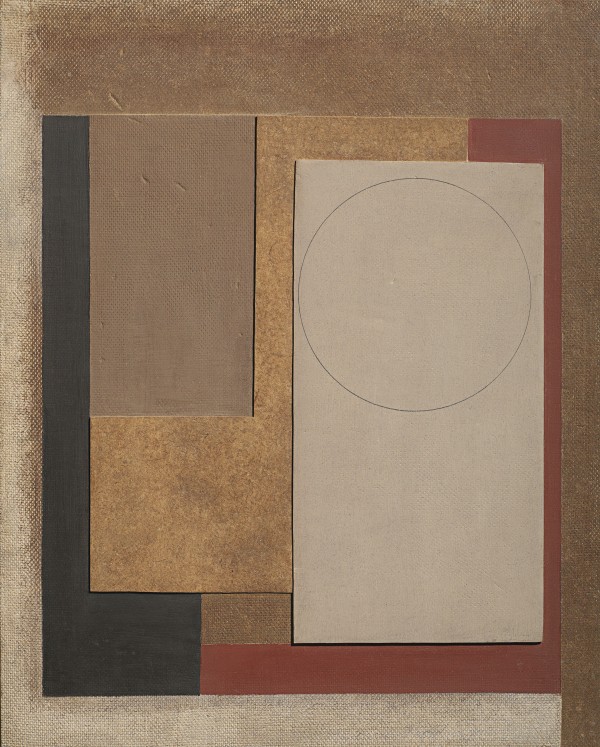

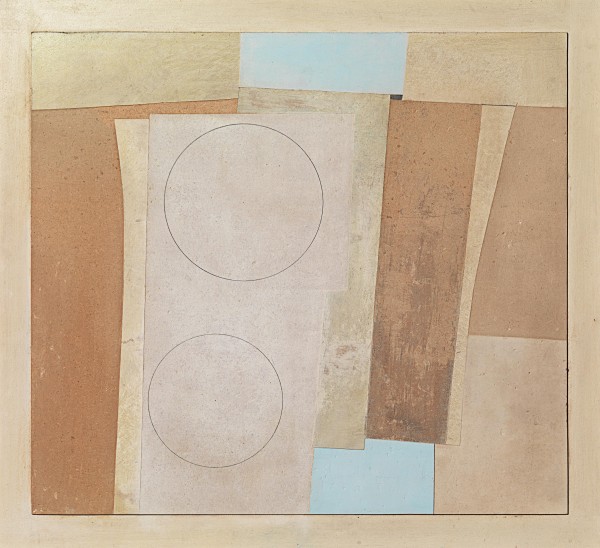

The original owner of Nov 25-46 (still life), Fred Staite Murray, was a major patron and friend of Nicholson. By the late 1940s Murray had amassed a significant collection of the artist’s painting from across his career, Nicholson would often ask him to lend works for exhibitions or to be photographed for publications. This would be the case for Nicholson’s 1947 show at the Lefevre Gallery, London; the exhibition from which Murray purchased the present painting for £100. The Lefevre catalogue – which Nicholson felt was “vital to the understanding of the sequence of v. early and late works”[iv] - lists 34 paintings from 1946-7, and 67 dating from the previous 25 years, with four pictures illustrated, including Nov 25-46 (still life). This retrospective framing of his most recent work was in keeping with Nicholson’s commitment to illustrating the coherence and reciprocity of his aesthetic priorities across what might be seen to be distinct periods in his oeuvre. In the years following the end of war this was a desire evident in Nicholson’s involvement in the first two books dedicated to his work, both published in 1948; the first, written by John Summerson, as part of the Penguin Modern Masters series, and the second a richly illustrated monograph with an introduction by Herbert Read published by Lund Humphries. As correspondence from the period attests, Nicholson’s contribution to the design and layout of the latter was extensive. Whilst the presentation of artworks is loosely chronological, the pairing and grouping of images across pages was carefully considered by the artist. Illustrated towards the end of the book, as one of the more recent paintings, Nov 25-46 (still life) is shown next to a 1945 abstract painting composed of two circles and overlapping lines.

In Nov 25-46 (still life), through complexity and balance, Nicholson achieves a carefully poised tension between line and form, flatness and texture, precision and gesture, qualities that would become integral to his abstract work over following decades. He would also observe that his still life paintings could often be identified more with landscapes, and his landscapes more with still life – a quality perhaps evoked by the weathered earthy tones of the present painting.[v] Produced at a pivotal moment in his career, in Nov 25-46 (still life) we are presented with a sophisticated synthesising of Nicholson primary aesthetic concerns, a painting that is visually contained, whilst eliciting a rich insight into his wider artistic practice.

Dr Lee Beard, 2025

[i] ‘The Life and Opinions of an English ‘Modern’’, Sunday Times, 28 April 1963, p.23.

[ii] Catalogue notes by Ben Nicholson, Ben Nicholson: a retrospective exhibition, Tate Gallery, London, 1955.

[iii] ‘Notes on Abstract Art’, in Herbert Read, Ben Nicholson, paintings, reliefs, drawings, Lund Humphries, London, 1948, p.27

[iv] Letter to Barbara Hepworth [7 May 1947], Tate Gallery Archive 20132.1.144.

[v] Statements: A review of British abstract art since 1956. Institute of Contemporary Art, London, 1957.