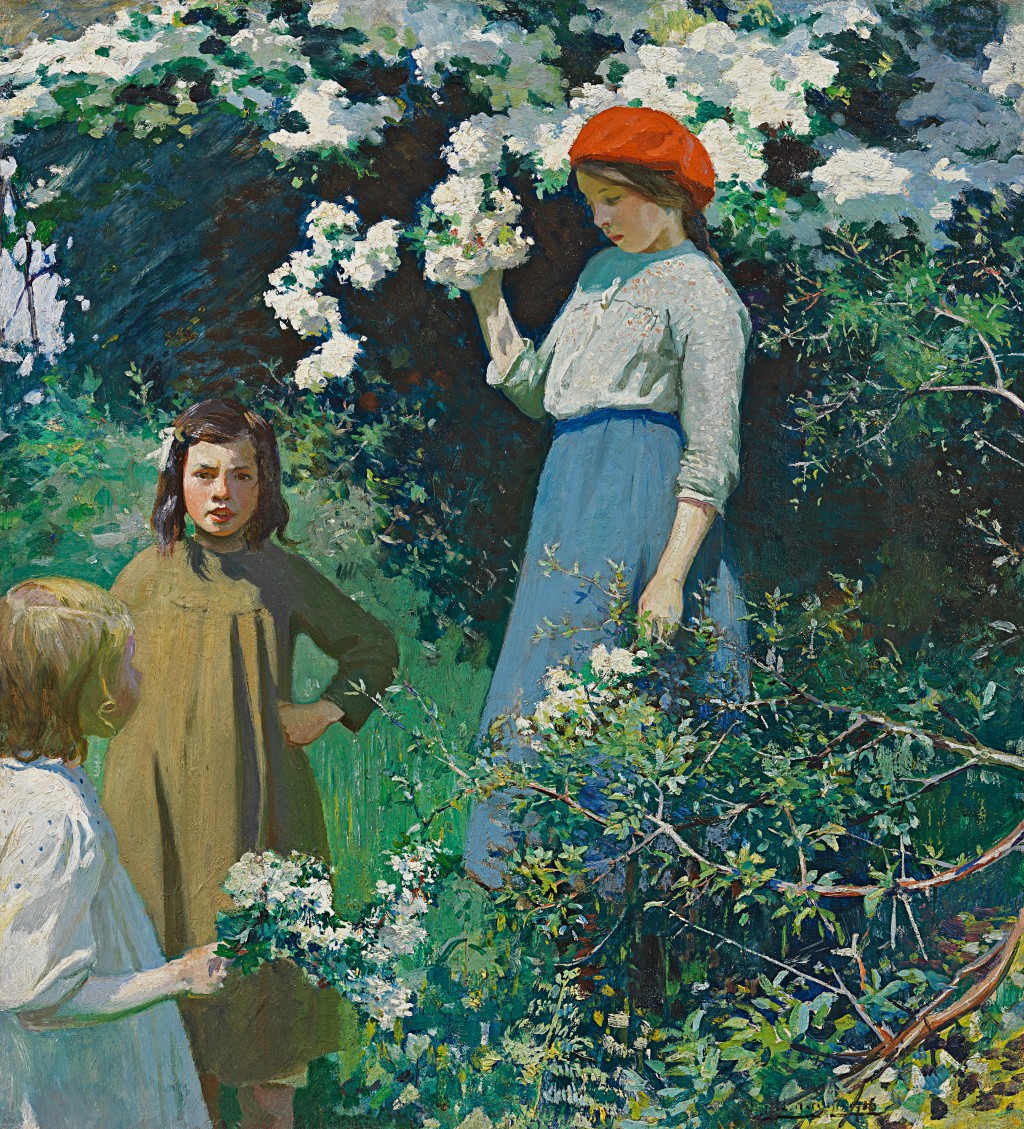

HAROLD HARVEY

Penzance 1874 - 1941 Newlyn

Ref: CD 144

Children among blossom

Signed and dated lower right: Harold . Harvey . 1916

On the reverse is another painting, Cattle in a farmyard

Oil on canvas: 20 x 18 in / 50.8 x 45.7 cm

Frame size: 26 x 24 in / 66 x 61 cm

In a reeded carved and gilded Whistler style oak frame

Provenance:

Queen’s Hotel, Penzance;

Phillips London, 13th November 1984, lot 69;

private collection, UK

Literature:

Kenneth McConkey, Peter Risdon, Pauline Sheppard, Harold Harvey: Painter of Cornwall, Sansom & Company, Penlee House Gallery & Museum, Penzance, revised 2024, no.291, p.127

On a hillside in Cornwall three girls, surrounded by blossoming shrubs, are standing talking. Touching the flowers, but giving them no attention, the eldest, wearing a red bonnet, looks down at the youngest. The little girl on the left looks up, as if to expect an instruction. Are these blooms worth gathering? In the middle, a girl in a brown smock dress looks straight ahead, as if addressing an unseen fourth member of the group. Scanning the painting, we suddenly become aware that the intense outward stare of this central figure is directed at us and the force of her gaze could almost be the picture’s undeclared subject.[1]

When he painted Children among blossom in 1916, Harold Harvey, was in mid-career and living close to his birthplace. All modern writers on the celebrated Newlyn School of painters make the point that he was the only truly Cornish member of the group, having been the son of a bank manager born in Penzance.[2] A regular supporter of the local Passmore Edwards Gallery in Newlyn, he had a formidable reputation in the south-west, with frequent solo exhibitions in Plymouth and Bristol, as well as at the Mendoza and Leicester Galleries in London.[3] A retiring individual devoted to his craft, he acted as an anchor for others in the post-1900 generation of artist-incomers to the south-west.[4] So strong were his roots, and so protected was his privacy, that biographers imply that he was immured against war and pestilence in the wider world. Affected by the death of his father in 1915, his painting en plein air in the fields around Penzance was inevitably restricted by wartime regulations forbidding the portrayal of coastal scenes. As a consequence, his current wartime subjects were almost exclusively interiors.

Thus, unusual for the year in which it was painted, Children among blossom returns Harvey to the flower and fruit harvests he had painted before the Great War. In this instance, however, the figures are observed in close-up and we only infer the Chywoone hillside from the fact the older girl stands on higher ground than her two companions.[5] Where once we might have a more conventional mise-en-scène with full figures close to the picture plane and others set back in space, as in Daffodils (fig.1), here all three form a cropped, close-up group.

Fig.1 Harold Harvey, Daffodils, circa 1912

Private collection, photo courtesy of Richard Green

Critics, one of whom referred to him as ‘l’homme orchestre’, noted that ‘his orchestration’ of ‘colour sounds’ was ‘so cleverly consistent’ that ‘numerous red stars’ testified to ‘public appreciation’. If it was sometimes remarked that Harvey’s children seemed disconnected and that their poses and expressions had little or no correspondence, this self-contained ‘aloneness’ must surely have been fully considered.[6] Sharper delineation and flat emblazoned colour was, by the war years, slowly replacing the early, more impressionistic handling, as the painter embraced the current fascination for ‘primitive Italian realism’.[7] The echo of Renaissance mastery would be seen most obviously in later ‘mother and child’ compositions of the twenties. Yet as is clear in the present picture, Harvey would only paint, according to Dod Procter, what he saw in front of him.[8] Young models would arrive at the Harvey house, Maen Cottage on Chywoone Hill, to be slipped a half-a-crown by Gertrude Harvey, before taking their place before the painter in a planned pre-existing ensemble.[9]

Unlike others of his school, there are no watersheds in Harvey’s career. His temperament was such that changes of style were gradual and premeditated. He was eclectic; he cast an eye on theirs and would know the meaning of placing one figure in a group that is looking directly out of the picture.[10] Piero della Francesca had done it; so too had Velázquez.[11] Fixed to floor by Harvey’s girl in brown in Children among blossom, the eye of the spectator reaches out. Thus captured, the so-called ‘one-man orchestra’, plays his song, and youth, like the wildflowers on a sunlit hillside, springs eternal.[12]

Kenneth McConkey, co-author with Peter Risdon and Pauline Sheppard of Harold Harvey: Painter of Cornwall, revised 2024.

[1] A work retrieved as part of the Queen’s Hotel collection in Penzance over forty years ago, it is possible that Children among blossom was originally sold to its owners under a different title. Twelve paintings by Harvey were included in the 1984 sale, including Summer milking (lot 66) for which the farmyard scene on the reverse of Children among blossom may have been intended as a companion. Harvey’s work entered a number of hotel collections in the south-west during his lifetime. When the Riviera Palace Hotel in Penzance closed in December 1917, his works appeared in the auction sale.

[2] See for instance, Caroline Fox and Francis Greenacre, Painting in Newlyn, 1880-1900, exh cat, Newlyn, Plymouth and Bristol Art Galleries, 1979 p.237, et al; see also the essential Kenneth McConkey, Peter Ridson and Pauline Sheppard, Harold Harvey, Painter of Cornwall, Sansom, Bristol 2001 (2024 reprint with additions by Ridson; herein ‘Ridson and Sheppard’, for which McConkey supplied the introduction).

[3] For Harvey’s support for the Passmore Edwards Gallery, opened in 1895, see Melissa Hardie, 100 Years in Newlyn, Diary of a Gallery, Patten Press in association with Newlyn Art Gallery, 1995.

[4] Without children or autobiography, Harvey’s keen recent biographers, Ridson and Sheppard, are often reduced to scraps that come from the accounts of contemporaries. Sadly, much is already lost.

[5] The spatial context is confirmed by the high horizon, indicated briefly on the left of the composition.

[6] ‘Arresting Pictures – L’Homme Orchestre’, The Morning Post, 25th October 1918, p.2.

[7] Op. cit., Ridson and Sheppard, 2024 ed., p.76; quoting ‘TIS’ [Herbert Furst], ‘About Harold Harvey’, Colour, October 1920, pp.48-54.

[8] Information supplied to Fox and Greenacre by Dr Hugh Hynes, c.1984; see also Alison James, A Singular Vision, Dod Procter 1890-1972, Sansom, Bristol 2007, p.40.

[9] Op. cit., Ridson and Sheppard, 2024 ed., p.62.

[10] For Harvey’s criticism of work by Dod Procter and Ernest Procter’s suggestion that he be banned from his wife’s studio, see James, 2007, pp.50-1.

[11] For the use of figures in groups, directly addressing the spectator in Piero, see Michael Baxandall, Painting and Experience in Fifteenth Century Italy, Oxford University Press, 1972, p.86; for Velázquez’ use of the soldier, a supposed self-portrait, looking out at the spectator in The Surrender of Breda (Las Lanzas), see Enrique Lafuente, Velázquez, Complete Edition, Phaidon Press, Oxford 1943, p.27.

[12] As note 5.