Jacob van Hulsdonck

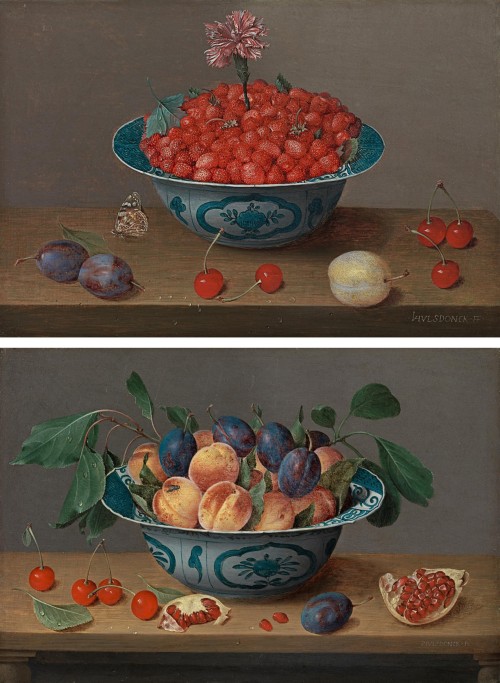

Still life of strawberries and a carnation in a Wanli porcelain bowl, with plums, cherries, an apricot and a Painted Lady butterfly (Vanessa cardui) on a wooden table

Oil on panel: 10.4 x 15.2 (in) / 26.4 x 38.7 (cm)

A pair, Signed lower right: IVHHVLSDONCK . FE (IVH in ligature)

This artwork is for sale.

Please contact us on: +44 (0)20 7493 3939.

Email us

JACOB VAN HULSDONCK

1582 - Antwerp - 1647

Ref: CB 208

/CB 209

Still life of strawberries and a carnation in a Wanli porcelain bowl, with plums, cherries, an apricot and a Painted Lady butterfly (Vanessa cardui) on a wooden table

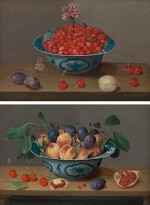

Still life of apricots and plums in a Wanli porcelain bowl, with cherries, a plum and a pomegranate on a wooden table

A pair

Both signed lower right: IVHVLSDONCK . FE (IVH in ligature)

Oil on panel: 10 x 15 in / 26 x 38.5 cm

Frame sizes: 20 x 15 in / 50.8 x 38.1 cm

Painted circa 1625

Provenance:

Private collection, Switzerland

Fewer than a hundred paintings by Jacob van Hulsdonck are known, from a career which spanned several decades. This may be because he painted with an extraordinarily high degree of finish and took a long time to complete each picture. Hulsdonck specialized in still life, mainly flower- and fruitpieces. This pair of paintings, of fruit in Wanli blue and white porcelain bowls, is very characteristic and a superb example of his work.

Hulsdonck’s bowls are placed on a wooden tabletop. In his earlier work, the viewpoint is quite high and the backgrounds dark. Later, he lowers the viewpoint, brightens the neutral background colour and often shows the edge of the table, giving a more naturalistic effect. This pair has comparatively light backgrounds and a low viewpoint, but no edge to the tables (except slightly in the strawberry painting), suggesting that they were made around 1625. In each work, Hulsdonck has made great play of the warm colours of the fruit against the cool, high-glazed hues of the Wanli bowls. The wild strawberries (fraises de bois) are a tour-de-force of observation, each tiny seed embedded in the scarlet fruit catching the light. In the top of the mound of strawberries, Hulsdonck has stuck a carnation. This motif occurs quite often in his bowls of fruit, for example in Wild strawberries and a carnation in a Wanli bowl, c.1620 (National Gallery of Art, Washington DC)[1]. The pink and white stripes and the serrated petals of the flower are exquisitely delineated. It is perhaps the complexity of carnations that appealed to Hulsdonck, as he painted a roemer filled with them in a painting in a private collection[2].

In the painting with plums and apricots, Hulsdonck contrasts the golden tones and fuzzy skin of the apricots with the smoother, deep purple plums, faithfully delineating the tiny blemishes on the fruit and the drops of water on an apricot and the leaves. A fly lands on one of the apricots, a reminder to Hulsdonck’s audience that corruption and decay will destroy even the most pristine products of nature.

The Chinese porcelain bowls were fashionable and precious objects in this era. The sixteenth century Portuguese dominance of the ceramics trade, shipped through their colony, Macau, was overtaken by the Dutch early in the following century. It became known as kraak ware from the Portuguese trading ships, carracas[3]. The Dutch East India Company (VOC) shipped Chinese blue and white porcelain from their own colony, Batavia (now Jakarta, Indonesia), a trickle which became a flood by the end of the century. Part of the fascination of hard-paste porcelain, with its white, translucent body, was that the technology behind it was a closely guarded secret, not discovered in Europe until the alchemist Johann Böttger achieved it in 1708. Hulsdonck does justice to the finely-potted vessels with their exquisitely thin rims and glowing, cobalt blue decoration, traced with auspicious and (to European eyes) mysterious Chinese symbols of nature and of good fortune.

An array of fruit is scattered along the tabletop in front of the bowls, beautifully delineated shadows adding to the trompe l’oeil effect. Particularly arresting are the pieces of pomegranate in the Apricots painting, where Hulsdonck evokes the glistening ruby seeds nestling in the creamy pith. In the Strawberry painting, a Painted Lady butterfly (Vanessa cardui) has just alighted on the table, a reminder of the countryside beyond the studio and the interrelationship of all things in nature.

JACOB VAN HULSDONCK

Antwerp 1582 – Antwerp - 1647

Jacob van Hulsdonck was born in Antwerp in 1582 and is reported to have received at least part of his training in Middelburg. Some sources say that he was a pupil of Ambrosius Bosschaert the Elder (1573-1621). He was also influenced by Jan Brueghel the Elder (1568-1625). In 1608 Hulsdonck was admitted to the Antwerp Guild of St Luke. He lived in the same house in that city from the time of his marriage to Maria la Hoes (d.1629) in the following year until his death, thirty-eight years later. In 1632 he married Josine Peters. Gillis, a child of his first marriage, also became a still life painter.

Despite his long career, not many still lifes - as far as we know his only subject - by van Hulsdonck are known to us, far fewer than a hundred. More than half of van Hulsdonck’s known paintings are signed with his characteristic full signature in capitals, the I linked to the obliquely placed left leg of the H to make up the V and usually situated to the left or right on the table’s edge. Some examples are signed with a monogram only, and only one dated painting is known thus far, an example of his earliest type of still life, painted in 1614: a banquet-piece, now in the Bowes Museum, Barnard Castle. In such early works, the table is partly covered with a white cloth; all of his later still lifes are set on plain wooden tables of which the grain of the wood is rendered with a high degree of detail. Occasionally these tables are partly covered with a dark (greyish- or greenish-black) cloth.

Although, owing to the of the lack of dated works, it is difficult to establish a firm artistic chronology, in general it appears that those still lifes by van Hulsdonck in which the edge of the table is close to the lower end of the picture plane and in which the tabletop is shown from a fairly high viewpoint belong to his earlier production. The side of the table is not shown in these still lifes. In what must be van Hulsdonck’s later works, some space is left under the table, usually one side of the table is shown, and the still life is viewed more frontally and in a slightly less rigid composition. Also, in the course of time the artist's colouring appears to have become less subdued and his backgrounds became less dark. Meticulous attention to detail is found throughout van Hulsdonck’s oeuvre and this may in part account for the restricted number of pictures he appears to have produced.

The work of Jacob van Hulsdonck is represented in the Mauritshuis, The Hague; the Museum Bredius, The Hague; the Rijksmuseum Twenthe, Enschede; the Bowes Museum, Barnard Castle; the Rheinisches Landesmuseum, Bonn; the Fine Arts Museums of San Francisco and the National Gallery of Art, Washington DC.

[1] Inv. no.2013.1.1. Oil on copper: 11 1/8 x 14 ¼ in / 28.3 x 36.2 cm.

[2] Carnations in a roemer, oil on panel: 33.7 x 24.5 cm. See Sam Segal and Klara Alen, Dutch and Flemish Flower Pieces, vol. I, Leiden 2020, pp.248-9, illus. in colour.

[3] We are very grateful to Ben Janssens of Ben Janssens Oriental Art, who comments: ‘These two broad-rimmed bowls depicted by Hulsdonck are of the very popular klapmuts type, so called because the shape resembles an upturned hat with a broad brim. They were among the first porcelains made for export to Europe. The Chinese themselves tended to prefer more refined, less decorated ware. The bowls in the painting are absolutely accurate and very recognisable as Wanli period porcelain for the Dutch market’.