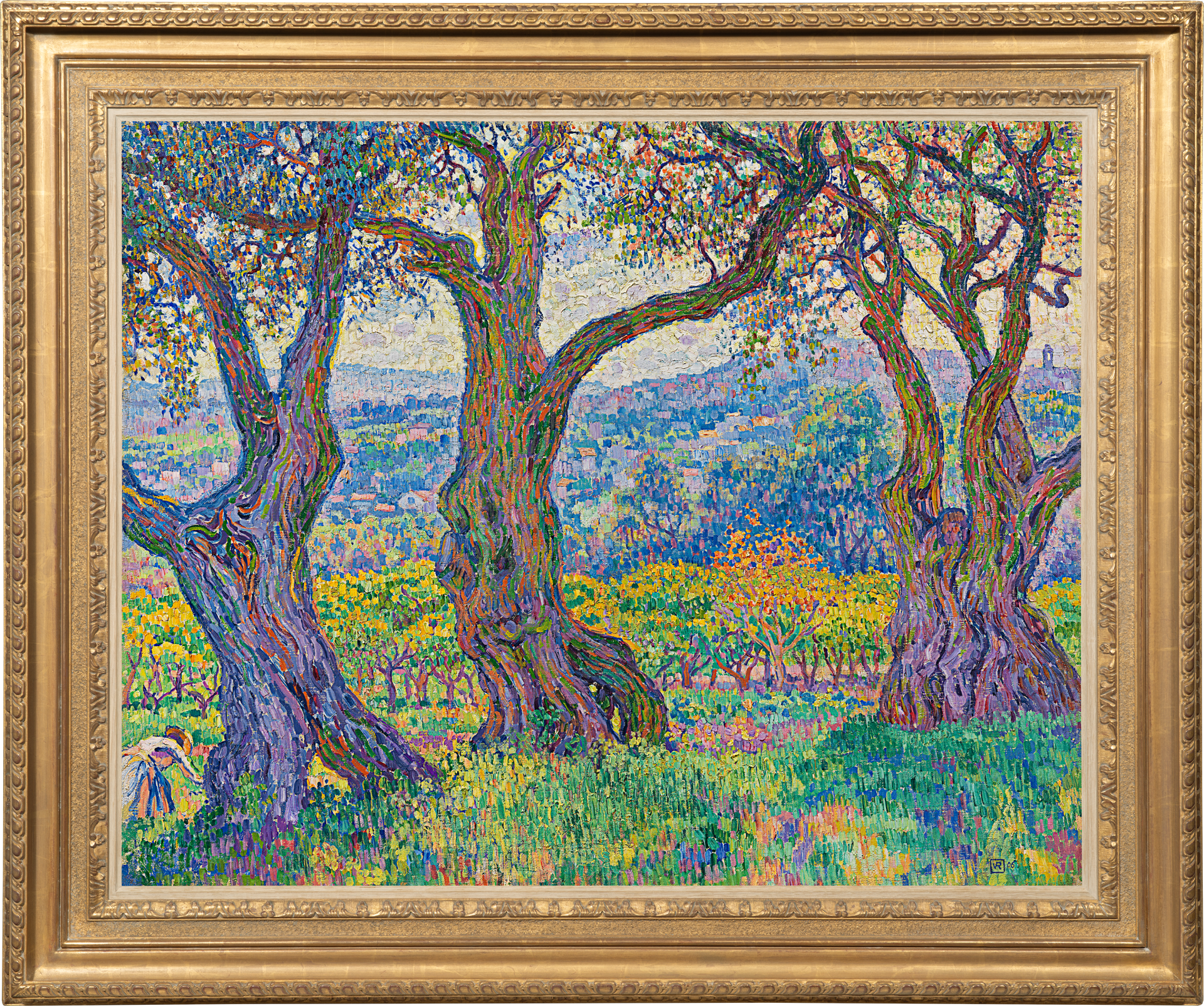

THEO VAN RYSSELBERGHE

Ghent 1862 - 1926 Saint-Clair

Ref: CD 137

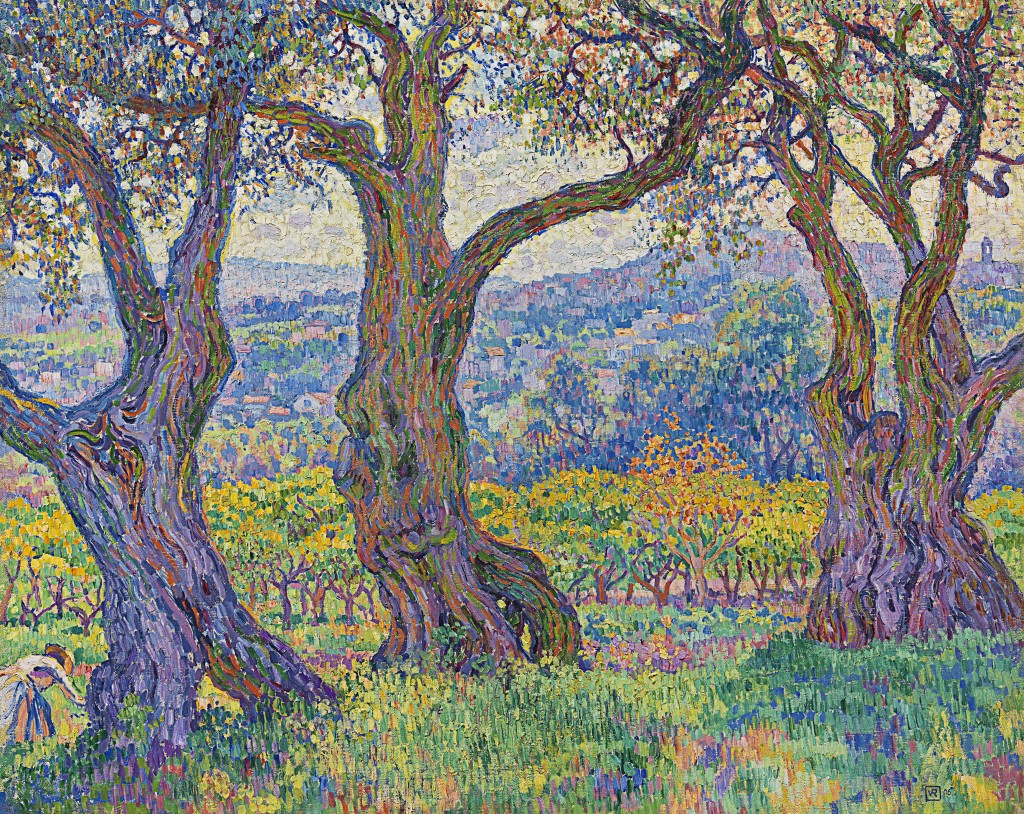

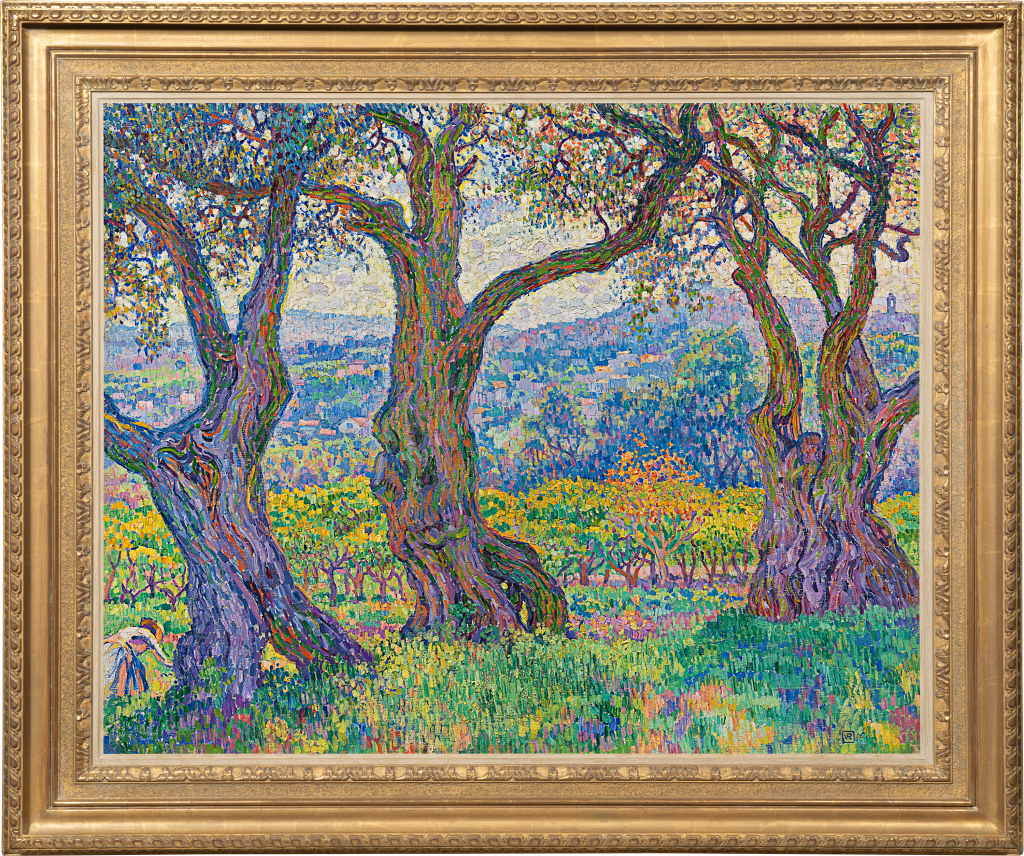

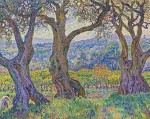

Oliviers à Cagnes

Signed with monogram and dated lower right: VR 06

Oil on canvas: 29 x 36 ½ in / 73.7 x 92.7 cm

Frame size:

Painted circa June 1906

Provenance:

Acquired from the artist by Gustave Fayet (1865-1925), Béziers

De Voogd-Nieboer

Galerie Georges Giroux, Brussels, 10th December 1928, lot 141 Henricus Nijgh (1873-1948), Rotterdam

Private collection, Europe;

by descent in 1995 to a private collection, Antwerp

Exhibited:

Ghent, Casino, Salon de Gand, 1906[1] Rotterdam, Rotterdamse Kunstkring, Théo Van Rysselberghe, 23rd October-21st November 1909, no.21 Groningen, Galerie Hofsteenge, Pictura Théo Van Rysselberghe, 16th January-2nd February 1910, no.18 Laren, Larense Kunsthandel, Théo Van Rysselberghe, February 1913, no.37 Paris, Galerie Druet, Sud-Est, 1927, no.50

Literature:

MS letter from Théo van Rysselberghe to Marie Closset, 13th June 1906

Ronald Feltkamp, Théo Van Rysselberghe 1862-1926, Brussels 2003, pp.104; 359, no.1906-021, illus.

To be included in the online catalogue raisonné in preparation by Mr Oliver Bertrand

This painting has been requested as a loan to the exhibition The Gustave Fayet Collection: Icons of Modern Art, to be held at the Louis Vuitton Foundation, Paris, from 26th September 2026 to 8th March 2027

Théo van Rysselberghe was an important conduit between Belgian and French Impressionism and Post-Impressionism. As a founder member of the avant-garde Belgian art association Les XX, he encouraged Paul Signac (1863-1935) to join; Georges Seurat (1859-1891) exhibited Un dimanche après-midi à l’Ile de la Grande Jatte, 1884 (Art Institute of Chicago) with them in 1887. Under their influence, van Rysselberghe became a leading exponent of Pointillism.

In the spring of 1892, distressed by the premature death of Seurat, aged thirty-one, the previous year, Signac sailed his yacht Olympia down to the South of France, accompanied by Rysselberghe. For both men, the light of the Midi was to prove a revelation. Signac thenceforth divided his time between Paris and Saint-Tropez, while Rysselberghe returned to the South of France almost every year. In 1911 his architect brother Octave designed for him a house at Saint-Clair, on the coast south-west of Saint-Tropez.

In this monumental painting of 1906, Rysselberghe turns his gaze away from the blue of the Mediterranean to the dazzling maquis of the countryside around Cagnes, a town between Antibes and Nice. (Cagnes was to become the private paradise of Auguste Renoir when he bought a small estate there the following year). Three ancient olive trees dominate the foreground, their writhing trunks imbued with almost anthropomorphic energy. Beyond is an orchard while, hazy in the distance, the terracotta roofs of the houses of Cagnes rise up the hillside. Almost hidden in this complex landscape, a woman at far left leans to pluck an unseen plant. She is the only human presence in a Mediterranean countryside tilled and shaped by man since Classical times, associated in the French psyche with an Arcadia in which humans lived in ideal harmony with nature.

By 1906 Rysselberghe had moved beyond his Pointillist phase to employ a more instinctive and varied brushwork, while developing a vivid palette influenced by Fauvism. Like Camille Pissarro, who also experimented with Pointillism in the second half of the 1880s, he ultimately found the method too restrictive. As early as 1899 Rysselberghe was writing to Signac: ‘Division, “pure colour” I never regarded as an aesthetic principle – still less as a philosophy – but solely as a means of expression’[2]. In Oliviers à Cagnes, the multicoloured shadows of the foreground grass are described with short, vertical strokes. Staccato bursts of vivid colour caress the gnarled contours of the venerable olives, emerald juxtaposed with orange, lilac against powder blue, conveying the heat and the pulsating light of the Midi. In the centre ground, the orchard is portrayed by dots of emerald and gold as the leaves rustle in the warm breeze. For the distant hills seen through the heat haze, Rysselberghe paints with a tessellation of horizontal dabs to evoke the roofs of the houses among the vegetation, using gentle tones of lilac, pale green, terracotta and grey-blue. The composition achieves both a naturalistic sense of recession and the abstract excitement of touches of colour dancing upon the canvas.

The impact and confidence of the work belies the fact that Rysselberghe found it a struggle to paint. On 13th June 1906 he wrote to his friend, the Belgian poet Marie Closset: ‘On that canvas is a view of Cagnes, seen through three enormous olive trees that together are about a thousand years old, their gnarled trunks full of holes, twisted and triumphant, which have given me no end of trouble! I am making a replica of that damned canvas, slightly larger and with more golden tones’[3]. Rysselberghe’s account of his struggle with the canvas could almost stand as a metaphor for his larger struggle to translate the truth of nature into paint. In seeking to portray trees that had stood on the hillside for hundreds of years, he is almost overawed by the grandeur of nature, but overcomes this to produce a painting of magisterial power.

In the larger version of Oliviers à Cagnes, 1906 (private collection)[4], the woman at the left has been replaced by two men working in the shade of the central olive tree.

Note on the provenance

Recent research by Yulia Kokurkina of the Louis Vuitton Foundation has established that this painting entered the collection of the artist, publisher and vineyard owner Gustave Fayet (1865-1925), probably soon after it was made. Fayet’s collection card in his family’s archives lists the work as ‘Olive trees in the foreground, their silhouettes set against a hill and luminous sky, with a woman on the left bending towards the earth’. Fayet’s interest in van Rysselberghe began in 1906 and they knew each other personally, as is proved by notes in Fayet’s journal and letters between the two men.

Born into a wealthy mercantile family in Béziers, Fayet was an entrepreneur and owner of several of the Languedoc’s finest vineyards. A keen painter himself, his passion for art was sparked by his father Gabriel Fayet. Gustave Fayet was a major collector of Impressionist and Post-Impressionist paintings, including works by Degas, Manet, Pissarro, Picasso and Redon.

We are very grateful to Yulia Kokurkina for kindly sharing details of her research on Gustav Fayet and Rysselberghe’s Oliviers à Cagnes.

Gustave Fayet (1865-1925).

THEO VAN RYSSELBERGHE

Ghent 1862 – 1926 Saint-Clair

Théo van Rysselberghe was born in Ghent in 1862 and studied at the Académie des Beaux Arts in Ghent under Théo Canneel. His brother Octave (1855-1929) became an architect. Théo continued his education at the Academy in Brussels where his teacher was the Orientalist artist Jean-François Portaels, who was to have considerable influence over the direction of his early career. At the age of eighteen van Rysselberghe made his debut at the Ghent Salon. In 1881 he exhibited for the first time at the Brussels Salon where he won a travelling scholarship to Spain, which marked the beginning of more than twenty years travelling in Europe, the Near East and North Africa. In 1882, at the end of this trip, he visited Tangiers and, fascinated by the atmosphere and colour of the city, he remained there for four months. On his return to Belgium Rysselberghe exhibited thirty paintings at the Cercle Artistique et Litéraire in Ghent, which were well received and brought van Rysselberghe’s work to the attention of both collectors and critics.

In 1883 Théo van Rysselberghe became one of the founder members of the group known as Les XX, sharing similar ideals with the Impressionists in France. Under the patronage of the lawyer and collector Octave Maus, Les XX was formed as a reaction to the strictures of academic art. James Ensor, Fernand Knopff, Félicien Rops, Auguste Rodin and Paul Signac were all members.

Van Rysselberghe became an important ambassador for the group and in 1886 travelled to Paris where he met the Impressionists and invited Renoir and Monet to exhibit in Belgium.

Van Rysselberghe’s visits to Paris and association with the Impressionists had a profound effect on his work and he began to produce works that were wholly Impressionist in nature. He was also deeply impressed by the work of the Neo-Impressionists and in particular Georges Seurat, whom he invited to join Les XX in 1887. He completely abandoned Realism and began to employ the theories of Pointillism, whilst still retaining his artistic ties with the Impressionists. Throughout this period he painted exceptional, highly worked portraits, landscape and seascapes using a palette of gentle pastel shades of blues, pinks and greens and generally employing short, curved brushstrokes rather than the staccato dots seen in the work of Seurat and Signac. He continued to travel and promote Les XX whilst at the same time extending his circle of friends. In 1889 van Rysselberghe invited Vincent van Gogh to participate in that year’s exhibition, where van Gogh sold Vigne rouge à Montmajour (Pushkin Museum, Moscow), the only firmly recorded painting to be sold in the artist’s lifetime. That same year Théo married Maria Monnom, heiress to the Monnom firm which published Jeune Belgique and L’Art moderne. During the 1890s van Rysselberghe turned his attention to the decorative arts, creating furniture, jewellery, stained glass and mural designs in 1895 for Siegfried Bing’s Parisian gallery Maison de l’Art Nouveau. In 1902 he painted a mural for Victor Horta’s Hôtel Solvay House in Avenue Louise, Brussels.

In 1897 van Rysselberghe settled in Paris where he became a regular contributor to the periodical Temps Nouveau. He was also commissioned to produce posters for the Compagnie des Wagons-Lits and as a result travelled across Europe, visiting Greece, Romania and Russia. During this time he met Pablo Picasso, although he was unimpressed by his work and advised Octave Maus not to purchase his paintings.

By 1903 van Rysselberghe had almost entirely abandoned the Pointillist technique; his brushstrokes became larger and more relaxed and, under the influence of the Fauves, he developed a stronger, more powerful palette. A visit to the South of France with Henri-Edmond Cross also had a deep and lasting effect on van Rysselberghe’s oeuvre: he became completely absorbed by the heat and light of the Mediterranean and devoted the rest of his career to painting sunlit landscapes and seascapes of the Côte d’Azur. He was often a guest at Signac’s house in Saint-Tropez. Van Rysselberghe built a house at Saint-Clair, near Le Lavandou, south-west of Saint-Tropez, in 1911, where he lived until his death in 1926, sharing his time with spells in Paris.

The work of Théo van Rysselberghe is represented in the Museum voor Schone Kunsten, Ghent; the Musées Royaux des Beaux-Arts de Belgique, Brussels; the Musée de Grenoble; the Kröller-Muller Museum, Otterlo; the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston; the Museum of Modern Art, New York; the Art Institute of Chicago and the National Gallery, London.

[1] This painting or possibly the second version, Feltkamp, op. cit., no.1906-022.

[2] Letter of 26th December 1899, Archives Cachin-Signac, Paris. Quoted in Brussels, Centre for Fine Arts/The Hague, Gemeentemuseum, Théo van Rysselberghe, 2006, p.66.

[3] Quoted in Ronald Feltkamp, op. cit., pp.104, 359.

[4] 35 ½ x 46 in / 90 x 117 cm. Feltkamp, ibid., pp.104-5, illus. in colour; p.359, no.1906-022, illus.