CAMILLE PISSARRO

Charlotte Amalie, Saint Thomas 1830 - 1903 Paris

Ref: CD 160

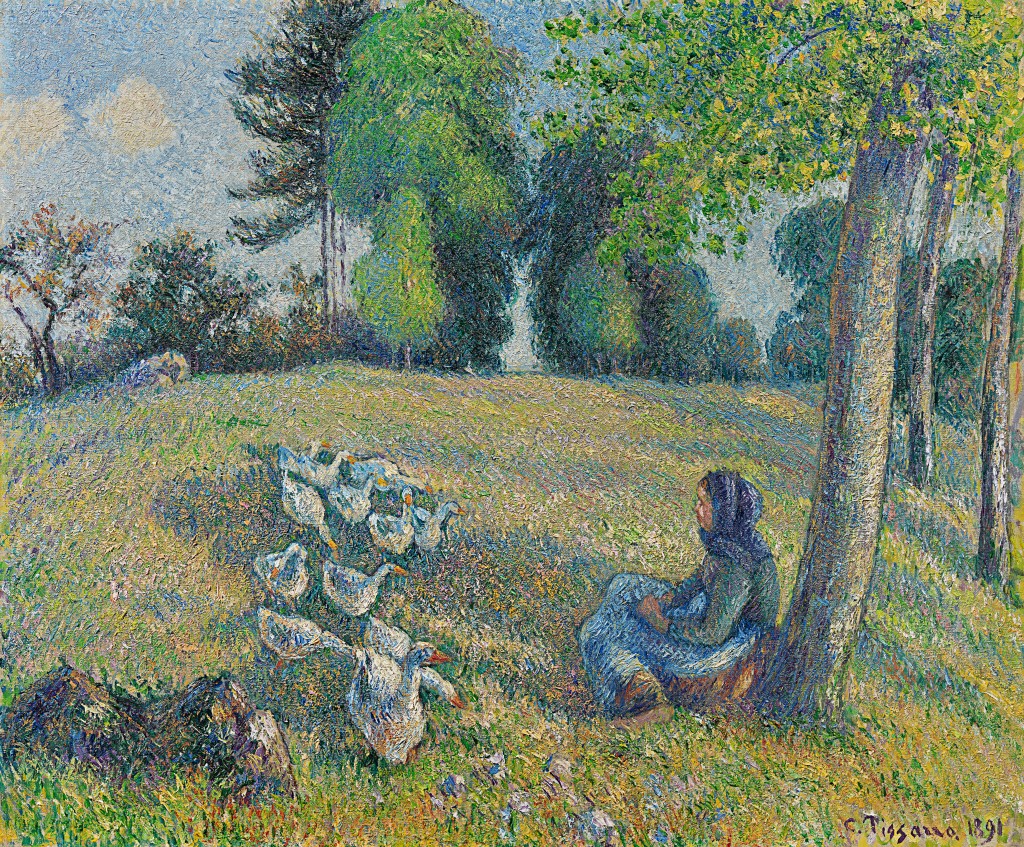

Gardeuse d'oies assise

Signed and dated lower right: C. Pissarro 1891

Oil on canvas: 21 ¼ x 25 5/8 in / 54 x 65.1 cm

Provenance:

Octave Mirbeau (1848-1917), Paris, acquired as a gift from the artist in October 1891;

by descent to his wife Alice Regnault (d.1932), Paris;

Hôtel Drouot, Paris, Succession de Madame Octave Mirbeau, 6th June, 1932, lot 7, illus.

Musée de l’Athenée, Geneva;

Arthur Tooth and Sons Ltd, London, acquired from the above on 2nd June 1955, inv. no.5127;

Sir Simon Marks, 1st Lord Marks of Broughton (1888-1964), acquired from the above in November 1958 and until at least 1963;

by inheritance to his daughter, The Hon Mrs Hanna Marcow, 1964;

Richard Green, London, 1994;

private collection, UK, 1995;

Richard Green, London, 2000;

private collection, USA

Exhibited:

Paris, Galerie Durand Ruel, L’Oeuvre de Camille Pissarro, April 1904, no.81

London, Arthur Tooth & Sons, Recent Acquisitions XIII, 1958, no.4, illus. (as Gardeuse d’oies)

London, Wildenstein & Co Ltd, The French Impressionists and Some of Their Contemporaries, 23rd April- 18th May 1963, no.7, illus.

Literature:

L’Art Vivant, March 1926

Ludovic-Rodo Pissarro and Lionello Venturi, Camille Pissarro: son art, son oeuvre, Paris 1939, no.770, pl. 159

Terence Kennedy, ‘Twelve favourite paintings’, The Connoisseur, vol. CXLVI, July-December 1960, p.250, illus.

Lucien Pissarro and John Rewald, Camille Pissarro: Letters to his Son Lucien, 4th edn. 1980, p.184

Janine Bailly-Herzberg, Correspondence de Camille Pissarro, vol. III, Paris 1988, p.123, letter no.690; p.124, letter no.692; p.125, letter no.693; p.150, letter no.715

Janine Bailly-Herzberg, Correspondance de Camille Pissarro, vol. V, Paris 1988, p.415, letter no. 2074

Pierre Michel and Jean-François Nevet, Octave Mirbeau. Correspondence avec Auguste Rodin, Tusson 1990, p.51, letter no.12; p.54, letter no. 13

Joachim Pissarro, Camille Pissarro, New York 1993, p.169, no.180, p. 169, illus.

Joachim Pissarro and Claire Durand-Ruel Snollaerts, Pissarro, Catalogue critique des peintures, vol. III, Paris 2005, p.604, no.918, illus. in colour

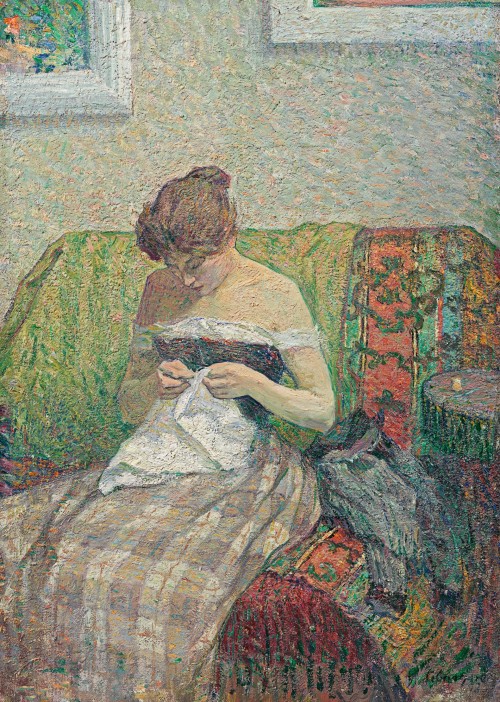

This beautiful painting of 1891 reflects the renewed energy of Camille Pissarro’s work in the 1890s after he had abandoned his brief experiment with Pointillism. Always open to new influences, he had met Georges Seurat in 1885 and was taken with his ‘scientific’ application of paint, in which dots of pure colour were scattered over a white ground, fusing on the eye to create the impression of a dazzling pictorial surface. Pissarro soon became disillusioned with the inflexibility of this method, writing to his son Lucien: ‘How does one obtain the qualities of purity and simplicity of the dot, with the fullness, suppleness, liberty, spontaneity and freshness of sensation of our Impressionist art?...the dot is meagre, lacking in body, diaphanous, more monotonous than simple’[1].

In Gardeuse d’oies assise Pissarro has moved away from the Pointillist dot towards a richly crosshatched impasto that balances animation and serenity. His palette contrasts violet-blue with emerald and chartreuse greens, interspaced with delicate pink and white. The gentle shadows of a summer’s day fleet across the lush meadow, evoked in myriads of tiny touches of interwoven colour. The goose girl sits quietly beneath a tree, the curves of her back and limbs infused with calm contentment. The gaggle of geese, coloured shadows playing over their pristine white feathers, provide a focus of animation with the varied attitudes of their sharp, orange beaks and their questing curiosity and noise. They also provide an important fulcrum for the composition, leading the eye back towards the line of trees. Pissarro had grasped the decorative value of geese far earlier in his career and in fact produced seven paintings on the theme of the goose girl, as well as many works on paper[2]. The earliest of these is La gardeuse d’oies à Montfoucault, 1876 (Museum of Fine Arts, Houston). He remarked: ‘I don’t want my geese to look like the real geese one puts in official genre scenes and illustrations…I conceive them as being unpolished, ornamental, complements to the composition, that’s all, but above all alive’[3].

In 1884 Pissarro had moved from the town of Pontoise to the village of Eragny-sur-Epte, where he became increasingly interested in the rhythms of rural life. Alone of the Impressionists, peasant life featured strongly in his landscapes, with figures coming increasingly into prominence. As an Anarchist, he believed devoutly in the dignity of labour and especially of the self-sufficient life of the peasants who answered to no master but maintained their smallholdings and sold their surplus produce in local markets. (Pissarro’s own family existence on his modest Eragny acres, ably directed by his wife Julie, echoed this mode of living). Pissarro’s peasants are not sentimentalized, like Millet’s, nor are they victims. As Richard Brettell has commented, ‘We never see…bodies broken down by work. Instead, they are strong and hardy rather than graceful and conventionally beautiful’[4]. The goose girl in this painting is serenely in command of her charges and in harmony with nature, her back against the slender tree, enjoying the light and shade shimmering across the grass and listening to the sound of the breeze.

Note on the provenance

This painting was a gift from Pissarro to the novelist and critic Octave Mirbeau (1848-1917), a champion of the Impressionists and Post-Impressionists. Pissarro had spent a day at Mirbeau’s country house at Les Damps, near Rouen, on 27th September 1891. Mirbeau wrote ecstatically about the work to Pissarro on 18th October: ‘The soul of nature is in all this, quivering and so loftily musical…What a poet you are, my dear Pissarro, and what a hard worker! And what I admire about your concept of art is that you never satisfy yourself with telling anecdotes. What breathes from your canvases is universal life, planetary life; in their reality there is always a splendid reaching out towards infinity’[5].

In the 1950s and 60s Gardeuse d’oies was in the collection of Sir Simon Marks, 1st Lord Marks of Broughton (1888-1964). Lord Marks built the small retail business that he had inherited from his father into the hugely successful British supermarket chain Marks & Spencer. The painting was inherited by his daughter, The Hon Mrs Hanna Marcow.

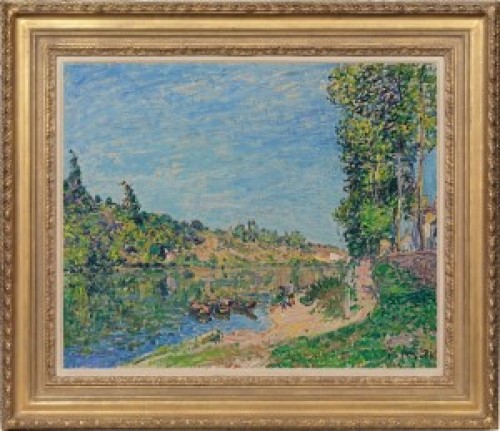

Camille Pissarro, La gardeuse d’oies, 1890.

Oil on panel laid down on paper.

Private collection.

CAMILLE PISSARRO

Saint Thomas 1830 - 1903 Paris

Camille Pissarro was perhaps the greatest propagandist and the most constant member of the Impressionists and the only one to participate in all eight of their exhibitions. Born in 1830 in the Danish colony of Saint Thomas[6] in the West Indies, of Sephardic Jewish parentage, he went to school in Paris and then worked in his father’s business for five years. Ill-suited to being a merchant, Pissarro decided to become a painter, studying at the Ecole des Beaux Arts and the informal Académie Suisse. He was considerably influenced and encouraged by Corot and to a lesser extent by Courbet.

During the 1860s Pissarro exhibited at the official Salons and in 1863 at the Salon des Refusés. He increasingly associated himself with the Impressionists, especially Monet and Renoir, and with the outbreak of the Franco-Prussian war in 1870 fled to London, where Durand-Ruel became his principal patron and dealer.

After the war, Pissarro returned to France and settled at Pontoise, spending much time with Cézanne, whom he directed towards Impressionism. In 1884 he moved to Eragny-sur-Epte. During the 1890s the meadows at Eragny, looking across to the village of Bazincourt, became one of Pissarro’s principal subjects, painted at different times of the day and year.

In 1885 Pissarro came into contact with Seurat and Signac and for a brief period experimented with Neo-Impressionism. The rigidity of this technique, however, proved too restrictive and he returned to the freedom and spontaneity of Impressionism. From 1893 Pissarro embarked upon a series of Parisian themes, such as the Gare St Lazare and the Grands Boulevards. He continued to spend the summers at Eragny, where he painted the landscape in his most poetic Post-Impressionist idiom. Pissarro died in Paris in 1903.

[1] Quoted in Sydney, Art Gallery of New South Wales/Melbourne, National Gallery of Victoria, Camille Pissarro, 2005, p.149.

[2] The paintings are Pissarro and Durand-Ruel Snollaerts, op. cit., no.472, 876, 893, 918, 1007, 1096 and 1324. They span from 1876 to 1900.

[3] Quoted in Pissarro and Durand-Ruel Snollaerts, ibid., vol. II, p.337.

[4] Richard Brettell in exh. cat. Fine Arts Museum of San Francisco/Williamstown, Sterling and Francine Clark Institute, Pissarro’s People, 2011-12, p.171.

[5] Quoted in Pissarro and Durand-Ruel Snollaerts, ibid., vol. III, p.604, no.918.

[6] Today part of the US Virgin Islands.