SIR JOHN LAVERYRA RSA RHA PRP NP IS

Belfast 1856 - 1941 Kilmaganny, County Kilkenny

Ref: CD 164

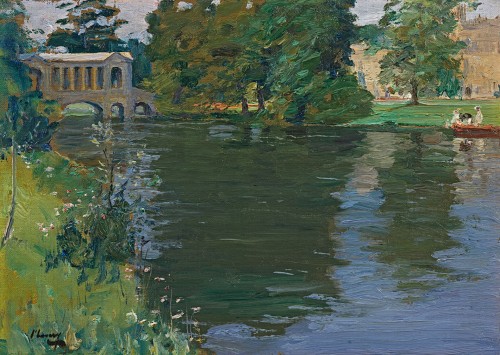

The Palladian Bridge, Wilton House

Signed lower left: J Lavery; signed, dated and inscribed on the reverse: THE PALADIAN BRIDGE . WILTON HOUSE .

1920 / BY JOHN LAVERY.

Oil on canvas laid down on board: 9 ¾ x 13 ¾ in / 24.8 x 34.9 cm

Frame size: 16 ½ x 20 ½ in / 41.9 x 52.1 cm

Provenance:

Private collection, acquired directly from the artist circa 1925, then by descent;

Phillips London, 26th November 1996, lot 42;

Frederick Gallery, Dublin;

private collection

Sotheby’s London, 13th May 2005, lot 51;

private collection

Christie’s London, 11th July 2013, lot 178;

private collection, UK

Exhibited:

Dublin, Frederick Gallery, Summer Exhibition of Important Irish Art, 16th June-4th July 1997, no.46, illus. in colour

Literature:

Kenneth McConkey, John Lavery: A Painter and his World, Atelier Books, Edinburgh 2010, pp.149, 235 (note 16)

Kenneth McConkey, Lavery On Location, exh. cat., National Gallery of Ireland, Dublin 2023, p.170

A day in August 1920 brought Lavery to Wilton House near Salisbury, the home of Reginald Herbert, 15th Earl of Pembroke and 12th of Montgomery. His primary purpose was to paint the celebrated Double Cube Room, designed by Inigo Jones in the seventeenth century to house Anthony van Dyck’s Philip Herbert, 4th Earl of Pembroke, and his Family, c. 1635, the Flemish master’s largest work (fig.1).[1] Faced with such complex and potentially confusing decoration, rich in its detail, Lavery rose to the occasion. Indeed, so enthused was he by its grandeur, that he substituted this fine ‘portrait-interior’ as his Diploma painting when he was simultaneously awarded full membership of the Royal Academy.[2]

Fig. 1 John Lavery, The Van Dyck Room, Wilton, 1920

25 x 30 in, Royal Academy of Arts, London

Seeing his current work in early September while reporting on Prince Albert’s visit to Wilton, the writer and gossip columnist for The Sketch, digressed into a call at Lavery’s studio. The artist had recently returned from the mansion and the room that contained ‘Van Dycks instead of wallpaper’. The full experience – ‘It’s quite clear he was interested up at Wilton’ – and was keen to show what he had achieved and talk about it, for ‘the charming painter’ had to be ‘enough interested in you to talk his best’.[3]

From one of the windows of the famous room, the artist must have caught sight of the famous Palladian Bridge over the river Nadder, a short distance from the house, and in the company of the countess’s daughter, Lady Patricia Herbert, determined to paint two small views of the structure. One shows the path leading up to the bridge, while the other, the present canvasboard, takes a view of the river span from the south bank (fig 2).[4]

Fig. 2 John Lavery, The Palladian Bridge, Wilton, 1920

9 ¾ x 13 ¾ in, Private Collection

Others before him had taken this path to view what, at the time of its construction in 1737, represented the height of taste for young English noblemen returning from the Grand Tour. Having studied Palladio’s style manual, The Four Books of Architecture, they knew exactly the effect they wished to achieve. Built by the nineth ‘architect’ Earl, the bridge follows Palladio’s pattern originally proposed for the Rialto, and such was its popularity that it was immediately copied for Lord Cobham at Stowe in Buckinghamshire, and others, such as that at Prior Park, Bath, followed. There was no more arcadian edifice to be found. Essentially a viewing platform, its fine classical proportions indicate that it was itself an ornament, designed to be viewed, and, as the present canvasboard indicates, married to the landscape. Everyone who visited Wilton admired it and many others had taken Lavery’s steps to obtain the best view. In the present instance he was following those of John Singer Sargent as he mounted the bridge around sixteen years before (fig.3).[5]

Fig. 3 John Singer Sargent, Sir Neville Wilkinson on the Steps of the Palladian Bridge at Wilton House, 1904/1905, watercolour, 14 x 10 in, Joseph F. McCrindle Collection, National Gallery of Art, Washington, 2010.93.3.

But where Sargent moved swiftly on, Lavery lingered, taking more time to place the structure in an agreeable composition.[6] The artist was instinctive and unerring in matters of this kind. From where he stood, Lavery was faced with the shimmering expanse of the river, flanked by tall trees in full leaf and beyond the tailored lawn on his right stood Wilton House, its warm east facing facade acting as a backdrop. Off to his right, on the opposite bank, a small group of figures had gathered - roughly at the spot where Winston Churchill produced his more conventional view of the bridge (fig.4).[7] Although we cannot be certain which of Churchill’s paintings were produced in Lavery’s presence, according to the Herbert family, a friendly rivalry existed between the master and his pupil.[8]

Fig.4 Winston Spencer Churchill, The Palladian Bridge, Wilton, circa 1920

25 x 30 in, The Earl of Pembroke, Wilton House

It is unclear when Lavery and the Herberts first met. In January 1920, however, while awaiting access to his villa and studio, the artist chanced upon the earl and countess accompanied by their daughter, Lady Patricia Herbert, at the Villa Harris in Tangier. Being familiar with the city, they showed their friends around, only to find, on one occasion that the car in which they were travelling was attacked by angry anti-French demonstrators during the bread shortages in the city.[9] This encounter may well have resulted in the invitation for Lavery’s visit.

Six months later, working on the present picture, the tensions of Tangier were a world away and Lavery’s exile to the far bank of the Nadder resulted in a work that carries all the qualities of more imposing canvases such as The Wharf, Sutton Courtenay 1916 (Hugh Lane Gallery, Dublin) and The Thames at Maidenhead, 1913 (Private Collection). A year later, in the catalogue of Lavery's exhibition at the Alpine Club Gallery, Churchill would describe Lavery as 'a plein-airiste if ever there was one, painting entirely out of doors, with his eye on the object and never touching a landscape in his studio … he is so quick that no coy transience of an effect can save it from his clutches … In consequence there is a freshness and natural glow about [his] pictures which give them an unusual charm'.[10] Garden scenes were at this point, much more Lavery’s forte than portrait-interiors and the concentration that carried him through the Van Dyck detail of the great saloon, was relaxed when he crossed the Palladian Bridge and, on the riverbank, found his ideal spot.

Kenneth McConkey, author of Sir John Lavery, a Painter and His World, 2010.

[1] The Saloon, or Double Cube Room at Wilton House, 30 x 30 x 60 feet, is in itself, regarded as Jones’s masterpiece.

[2] McConkey 2023, p.170. Lavery initially intended to submit a portrait of his wife, Hazel Lavery, to the Academy. For some time, he had been developing a minor specialism in ‘portraits’ of specific interiors, to be drawn together in a themed exhibition in 1925.

[3] ‘More about Mariegold’, The Sketch, 22nd September 1920, p.281. Had he or she stayed a little longer, the Sketch writer concluded, Lavery might have been able to paint the Duke of York at Wilton. Prince Albert, Duke of York, then aged twenty-five, later became King George VI. In addition to The Van Dyck Room, Wilton, the writer is likely to have been shown the present work.

[4] Fig.2 was apparently a birthday gift from the artist to Lady Patricia Herbert, later Viscountess Hambledon.

[5] Richard Ormond and Elaine Kilmurray, John Singer Sargent, The Later Portraits, Complete Paintings Volume III, Paul Mellon Centre for British Art, Yale University Press, New Haven 2003, p.137, no. 480.

[6] For this the painter took his painting kit to the south bank of the river, approximately 150 yards from the bridge.

[7] Gifted to the Earl of Pembroke by Lady Churchill after her husband’s death, Fig.4, (Coombs 1967, and 2011, no.121, p.109), is one of five views of the bridge by Churchill, one of which is in the Royal Collection.

[8] Churchill had become Lavery’s pupil in 1915 (see McConkey 2010, p.149; Coombs 2020, pp.22-26). Clearly, while Churchill’s understanding of Lavery’s practice was, by 1920, profound, his practical ability lacks the suavity of the present work.

[9] According to Hazel Lavery, they pulled at Lady Pembroke and her cloaks and battered the car with sticks, until they realized that she and her companion were not French (letter dated 29th January 1920, Private Collection). This frightening experience, coupled with widespread evidence of French colonisation of the city, encouraged Lavery to sell his studio in Tangier. Although they remain unidentified, it is likely that the figures in In Morocco 1920 (sold Bonhams 30 June 2021) are those of the Herberts.

[10] Winston S Churchill, ‘Foreword’, in Pictures of Morocco, the Riviera and other scenes by Sir John Lavery RA, with Portrait and Child Studies by Lady Lavery, exh. cat., Alpine Club Gallery, London 1921, pp.3-4.